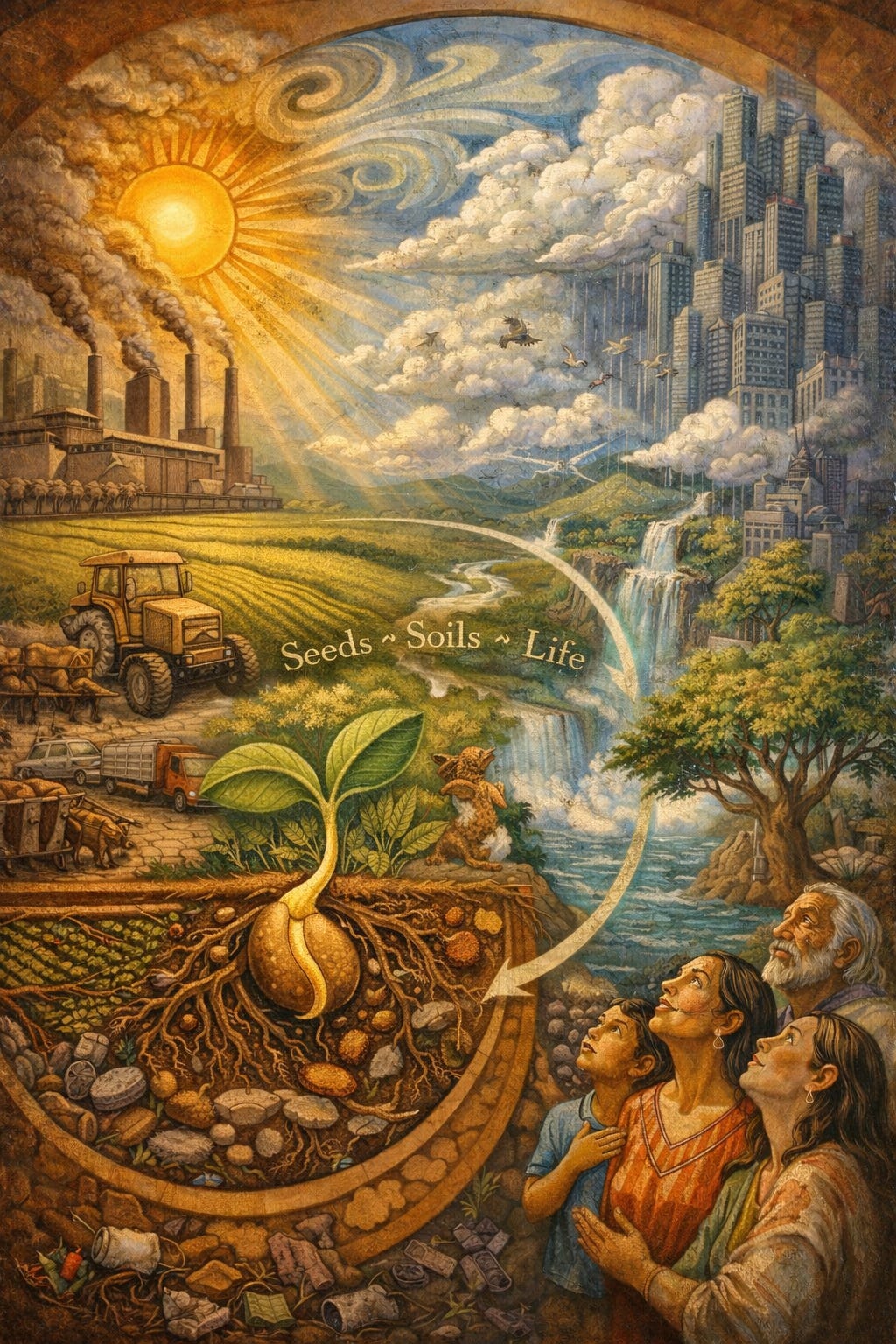

Prelude To A Paradigm Shift Via Seeds & Soils

Seeds At 400 Million Years & Counting Have Been Here A Little Longer Than Us.

Overview

Firstly, our apologies if this headline looks sensational, this is not our style, at all. This lead-in article does introduce some emerging concepts, the coming together of which will give us deep resilience in our food-systems and where they reside.

There is a simple truth so foundational that it is often overlooked:

Plants feed soils first, and humans only second.

This is not metaphor.

It is not philosophy.

It is not a moral claim.

It is biology.

Every meal any human has ever eaten sits downstream of this ordering. So does every village, every city, every economy, and every civilization that has ever existed.

At this point in time, it is beyond tragic that a focus on investment portfolios is seen as far more important than the security of our fragile food systems. So what do we do about this. We have plans, which we intend to enact upon and also extend, so please read on.

The quiet work beneath our feet

Plants do not grow from soil.

They grow with soil.

Through their roots, plants release sugars, amino acids, enzymes, and organic acids into the surrounding earth. These substances are not waste products; they are exchanges. They feed bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and countless unseen organisms that live in the narrow zone where roots and soil meet.

In return, those organisms mobilize minerals, fix nitrogen, store carbon, build soil structure, and regulate the movement of water and air through the ground. Only after this living economy is functioning do leaves, fruits, grains, and roots appear — the parts we recognize as food.

So when humans eat plants, or animals that eat plants, we are secondary beneficiaries of a much older and deeper relationship. Long before agriculture, long before cities, long before markets, plants were feeding soils so that life itself could continue. Some studies note that spores first emerged almost 1 billion years ago and seeds around 400 million years ago. So the ongoing futile efforts of human beings regarding the controlling of seeds are just that; futile. We view the emergence of hybrids as unnecessary and the meddling of seeds via genetic modification as dangerous and immoral when that results in innocent farmers being persecuted.

Seeds: how life learned to wait

Nearly ninety percent of all plant species on Earth are seed plants.

Seeds are not merely reproductive units. They are time capsules of life. They allow plants to pause growth, to wait through drought, cold, fire, or flood, to travel across landscapes and generations, and to re-enter the world when conditions are right.

Because of seeds, plants survived ice ages and climate upheavals. Soils deepened instead of eroding away. Forests emerged, grasslands stabilized, and complex land-based life became possible. Seeds allowed life to say, quite literally, not now — but later.

Human agriculture did not invent this system. It merely stepped into it, very late in the story, borrowing an evolutionary strategy refined over hundreds of millions of years.

The great forgetting

Modern food systems often treat soil as an inert growing medium, something to be amended, corrected, or managed through inputs. Soil is framed as a container rather than a collaborator.

But soil is not a container. It is a living commons.

When we reverse the natural order — feeding plants directly with synthetic nutrients while starving the soil communities that make life possible — we can still produce food for a time. But we do so by drawing down biological capital rather than renewing it.

This forgetting is rarely intentional. It happens through abstraction. Food becomes yield. Yield becomes commodity. Commodity becomes price. Price becomes policy. And somewhere along that chain, the living system beneath our feet fades from view.

Meanwhile, the soil grows quieter and this is not just soil in million acre monocultures, it is also the soil which underpins every village, town and city on Earth. Soils which we have covered with concrete, tarmac etc, etc.

A wider lens than humanity

Every human being depends on food systems to survive beyond a few weeks.

But humans are not the only participants.

Food systems include pollinators and fungi, soil microbes and insects, birds and grazing animals, water cycles and atmospheric exchanges. These non-human participants are not peripheral. They are central. They do most of the work.

When we speak of food systems as purely human affairs, we erase the majority of contributors. Plants do not grow food for us. They grow in relationship with the Earth, and we are allowed to eat because that relationship holds.

Why this matters now

Urbanization, climate instability, soil loss, and highly centralized supply chains have exposed how fragile food systems become when they forget their biological foundations.

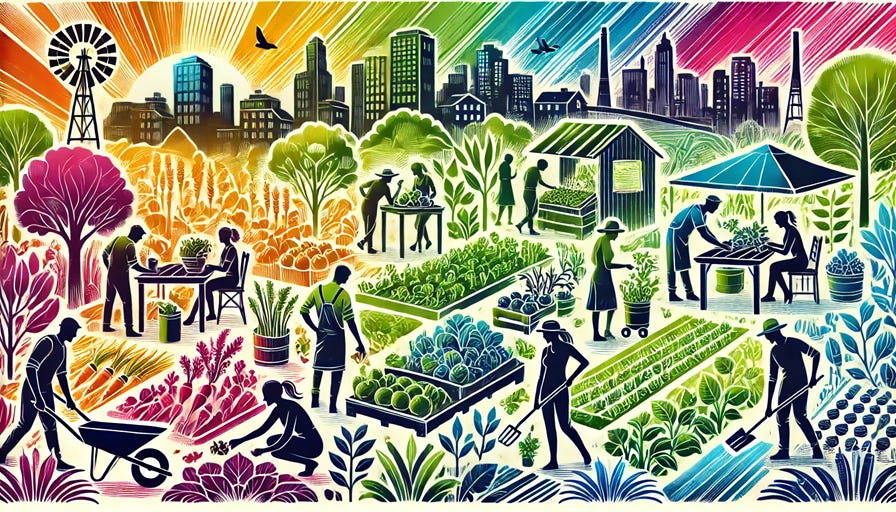

And yet, alongside this fragility, something else is quietly happening. Gardens are appearing in cities. Seeds are being saved again. Nitrogen-fixing plants are returning to landscapes. Soils are being rebuilt where people live. Our next article with amplify Incredible Edible Cities and Fabaceae Food Forests, a truly potent combination.

These are not nostalgic gestures. They are biological corrections. Life reasserting patterns that work.

Next Steps

In recent months, even mainstream policy and media outlets have begun calling for what they describe as “unconventional” solutions to food insecurity and ecological strain. These proposals range from alternative protein sources to radically different growing environments, often framed as novel or disruptive ideas. Yet what is striking is that many of these so-called unconventional approaches are, in fact, attempts to rediscover biological efficiencies that long predate industrial agriculture. They are signals that the dominant food system is struggling to reconcile itself with physical limits — soil loss, water scarcity, energy intensity — and is searching, sometimes awkwardly, for ways back into alignment with living systems.

What this moment reveals is not a lack of innovation, but a misdirection of attention. The most resilient food solutions are not necessarily exotic or technologically complex; they are often spatially local, biologically grounded, and socially embedded. This is where ideas such as Incredible Edible Cities quietly re-enter the conversation — not as aesthetic projects or community hobbies, but as serious food-system infrastructure. When food is grown where people live, using plants that build soil rather than deplete it, cities cease to be mere endpoints of consumption and begin to function again as living participants in ecological cycles.

A necessary re-ordering

If we begin with the truth that plants feed soils first, then several consequences follow naturally. Soil health becomes primary rather than optional. Seed diversity becomes a form of resilience rather than a luxury. Food systems begin to look like ecological systems again. Cities start to be seen not only as places that consume life, but as places that can grow it.

This understanding opens the door to more specific explorations — including how particular plant families, and particular approaches to urban design, can help restore this ordering in practical, grounded ways.

Those explorations will come next. Our next articles with amplify Incredible Edible Cities and Fabaceae Food Forests, a truly potent combination.

FMNR: When Forests Remember Themselves

There is a form of regeneration now quietly re-emerging across degraded landscapes that does not begin with planting at all, but with recognition. Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) works by protecting and guiding the living root systems, dormant seeds, and coppicing stumps already present beneath exhausted soils. What appear to be shrubs or wasteland are often forests held underground by grazing, fire, and disturbance, waiting only for pressure to be lifted. In this way, FMNR mirrors the role of Fabaceae in food forests: legumes feed soils forward through nitrogen fixation, while regenerating trees feed soils backward through memory, depth, shade, and water cycling. Together they form a bridge between past resilience and future fertility — one stabilizing soils, restoring hydrology, and rebuilding biological structure without imported inputs, machinery, or abstraction. The forest was not absent; it was interrupted mid-sentence.

As mentioned a few times in this lead-in article, our next one will get very detailed around the subjects of:

Fabaceae Food Forests

FMNR

Urban Food Production Via Incredible Edible Cities

For now, this is enough to hold:

Most plants depend on seeds.

Most soils depend on plants.

All humans depend on soils —

even when they forget it.