The Artificially Created Seed World

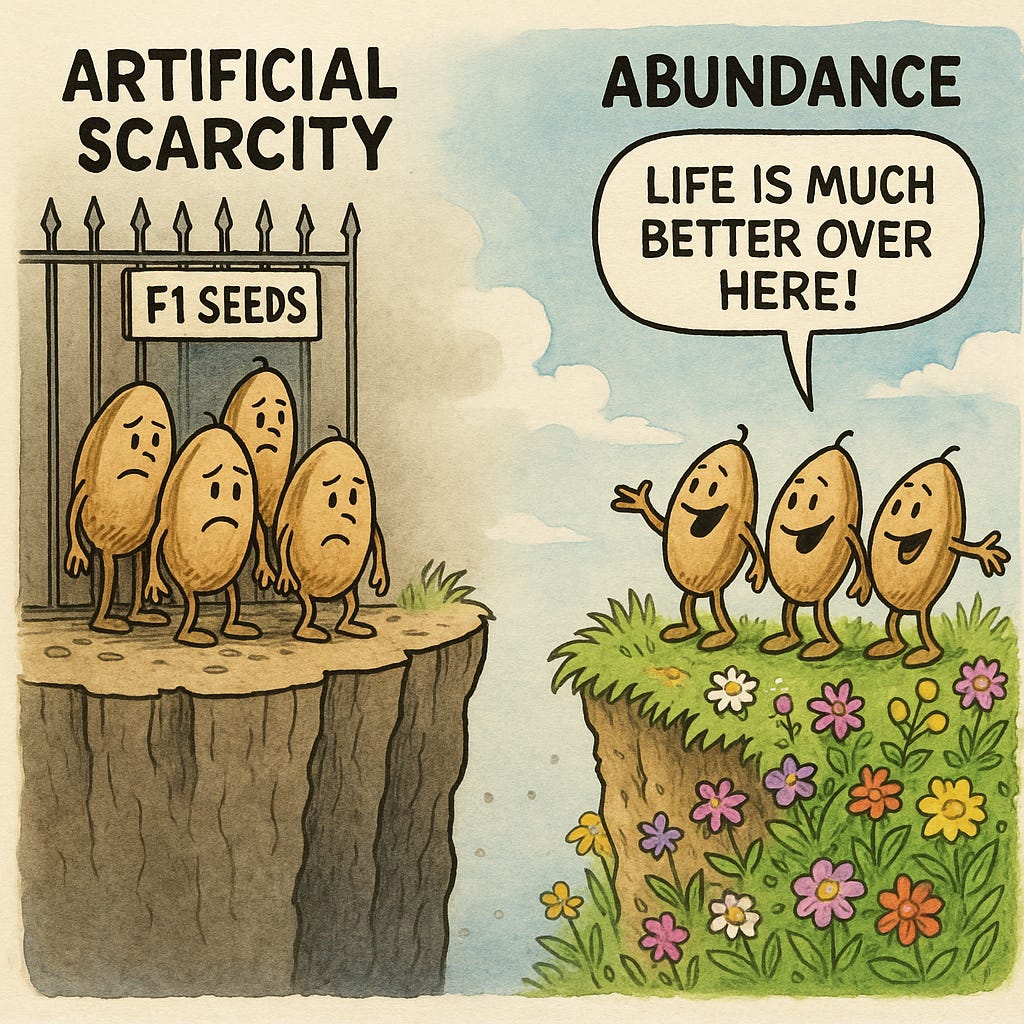

Seeds Are Not Scarce By Nature (Literally).

Here’s the nutshell version:

Artificial scarcity in seeds isn’t just an accident — it’s a product of legal, economic, and biological design choices.

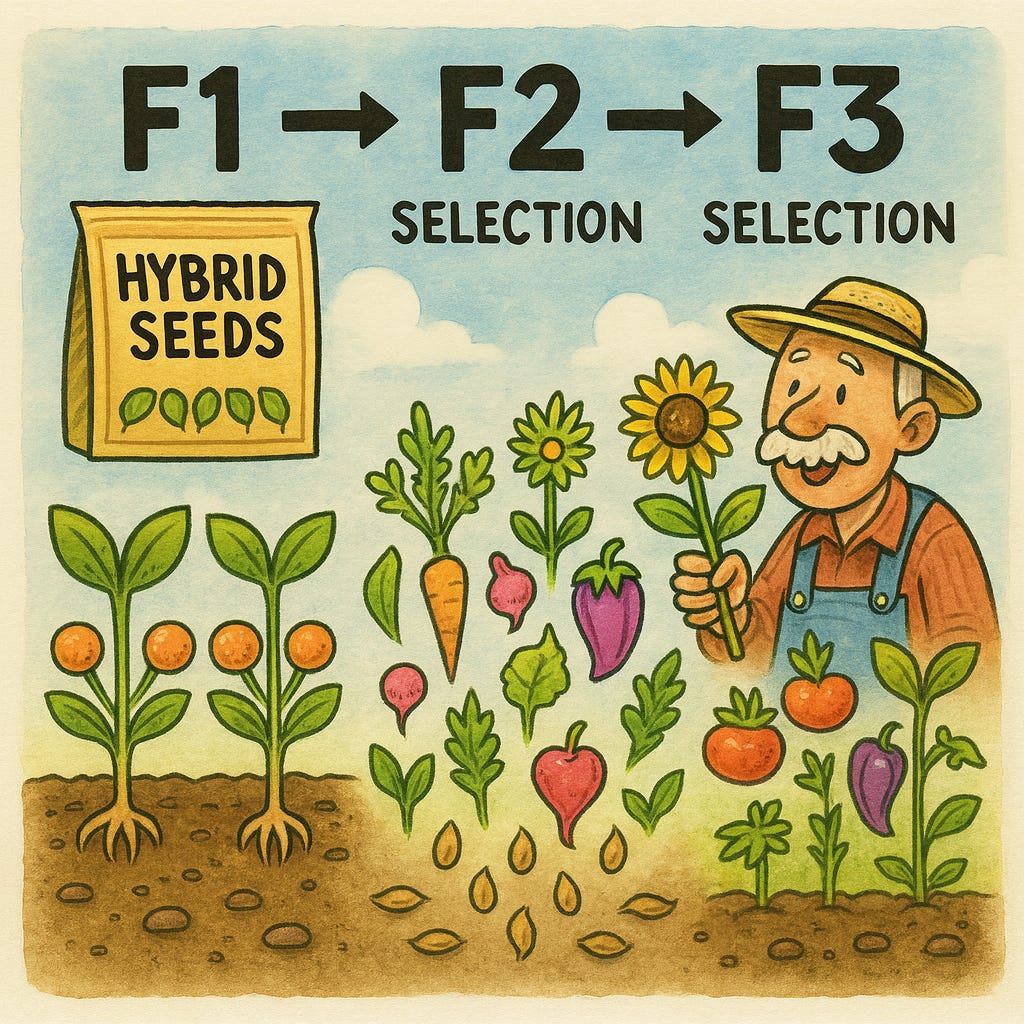

F1 seeds are the first generation from a deliberate cross between two stable parent lines. They often have hybrid vigor (fast growth, strong yield), but their offspring (F2 and beyond) will segregate into multiple forms — which is why commercial growers buy F1 seeds every year.

On one side, GMO and hybrid seed systems are marketed for higher yields, pest resistance, or other traits, but they often come with patents or “terminator” technologies that prevent farmers and gardeners from saving viable seed.

On the other side, “true-to-type” assurances in commercial seed packets appeal to gardeners who want dependable, predictable results — but these assurances sometimes rely on controlled pollination isolation and strict variety ownership, which also limits the free flow of genetic diversity.

Saved seeds have virtually no value, if fact, they are often looked down upon. Yet, traditional societies prized Landrace-saved seeds over millennia.

The result is a narrowing of seed sovereignty — where fewer people have the ability to save, share, and adapt seeds locally. This goes directly against the natural resilience of plants, which evolved to adapt to specific microclimates over time through open pollination.

F1 Generation: The Hybrid Starting Point

The origin of F1 hybrids wasn’t about packet retail seed sales to home gardeners (that came much later). The motivation was rooted in agriculture, genetics research, and economics going back over a century.

Origins of F1 Hybrid Seeds

Discovery of Hybrid Vigor (Heterosis) — Early 1900s

Plant breeders noticed that crossing two distinct inbred lines of crops often produced offspring that were healthier, faster-growing, and higher yielding than either parent.

This was especially studied in maize (corn) in the U.S. around 1908–1920.

Early corn hybrids demonstrated 20–50% yield increases compared to open-pollinated landraces.

Industrial Agriculture Needs

By the 1920s–30s, the U.S. (and soon other countries) wanted predictable, uniform crops that could be harvested efficiently and fit into a mechanized food system. A mechanized food system which increasingly relied and relies heavily on Fossil-Fuel inputs. Yet despite contending rhetoric, Fossil-Fuels are finite and will decline in affordable extraction.

Open-pollinated varieties (landraces, heirlooms) were diverse → great for resilience, but not ideal for machine harvesting or uniform processing.

Hybrids solved this by producing crops that were uniform in size, timing, and quality.

Seed Company Economics

Once farmers realized F2 seeds (saved from hybrids) gave inconsistent, lower-yielding plants, they had little choice but to buy fresh F1 seed each season. To paraphrase Al Gore in a related documentary “An Inconvenient Truth”.

This was not accidental: it became a built-in business model.

Farmers no longer saved their own corn and other seeds; seed companies gained a permanent market. Bill Mollison (co-creator of Permaculture) noted this back in the 1980’s, yet he was largely ignored.

Can We Evolve A De-Hybridizing Seed Protocol?

Turning F1 Hybrids into Locally Adapted Open-Pollinated Varieties

And why would we do this? Well our current industrially focused agricultural systems are deeply flawed: how?

Firstly, food-supply distances. This article from December 2024 highlights the fragility of long-distance food supply systems “Velocity is imperative: Supply chain distances and times have increased a great deal (more in some corners of the world than others), and so have the challenges involved in getting fresh produce from source to destination before spoilage renders it unsalable.”

Next the loss of generationally and regionally curated seeds, often called “Landraces” over millennia. Joseph Lofthouse writes of this and related subjects in articles that can be found here. “Adaptation agriculture is an intimate relationship between a location, a farmer, and a population of genetically-diverse seed. An adaptivar landrace is a foodcrop containing lots of genetic diversity which tends to produce stable yields under marginal growing conditions. Landrace crops are adaptively selected via farmer choice and survival-of-the-fittest for reliability in tough conditions. The arrival of new pests, new diseases, or changes in cultural practices or in the environment may harm some plants in a landrace population, but with so much diversity many plants are likely to do well under the changing conditions.”

Purpose Of De-Hybridizing Seeds

To reclaim hybrid seed varieties from dependency on annual purchase, adapt them to local climates and soils, and return them to the community as stable, open-pollinated varieties within 5–7 growing seasons.

Core Principles

Variation is a gift — early generations will be diverse; this is the raw material for adaptation.

Selection is the engine — our choices shape the variety’s future.

Diversity across locations speeds adaptation — multiple gardens mean more environmental filtering.

Documentation ensures inheritance — without records, knowledge is lost. Fortunately we created a web-based system called Permaledger which we adapted from the farmOS open source project. We have now been using this for 5-6 years so it is replete with information.

Community keeps the commons alive — seed should remain freely available.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Phase 1 – Identify & Acquire F1 Seeds

(Note that our current Cascadia Seed Guild Seed Bank holds 2,266 varieties of seeds and we have many F1 Hybrids to select from).

Select hybrids worth reclaiming based on:

Flavor & nutrition

Productivity

Local market/cultural importance

Climate suitability potential

Record initial variety info in Permaledger:

Seed source, year, lot #

Claimed traits

Growing requirements

Phase 2 – Grow Out F1 Generation

Plant in multiple plots if possible (different soils, exposures).

Grow as you would any crop, but do not select yet — this generation is genetically uniform.

Save seed from as many plants as possible to maximize genetic base.

Store seeds using our local low-cost storage protocol.

Phase 3 – F2 Generation: The Big Split

Plant lots of seeds (minimum 30–50 plants, ideally >100 for broad diversity).

Expect wide variation — growth habit, fruit shape, yield, disease resistance.

Selection criteria: Choose plants that:

Thrive in our climate/soil

Match desired use (eating fresh, storage, canning, etc.)

Show resilience to local pests/diseases

Taste great (if applicable)

Tag selected plants before harvest.

Record all traits and environmental notes in Permaledger.

Phase 4 – Stabilization (F3–F5)

Plant seeds from selected plants only.

Continue selecting for target traits.

Distribute to other community gardens to test adaptability.

Cross-reference results between locations in Permaledger.

Each year, aim to narrow variation without bottlenecking diversity too quickly.

Phase 5 – Local Variety Release (F6–F7)

By now, plants should be largely true-to-type (>90% consistency in target traits).

Name our new open-pollinated variety — ideally with a local place or cultural reference.

Add to community seed bank & seed library with:

Full history

Growing notes

Best use cases

Publicly release as open-source seed (for instance; via Open Source Seed Initiative pledge).

At this point, we have a large Seed Bank from which we can select many F1 varieties. However, this is still in the proposal phase and we are in no way wanting to negatively impact any genuine participants in our current food-seeds realms. However, we believe that becoming more resilient and localized in our food-systems is an incredibly important legacy to leave to our descendants.

Thank you as always for reading this and please feel free to comment here.